'Concentration camp literature'… in the CegeSoma Library

'Concentration camp literature'… in the CegeSoma Library ... Under this title, we invite you to discover the sixth theme of our series 'The Librarian's talks'. Each theme will be the occasion to dive into our collections and will be illustrated by a video and a text to complete the information contained therein.

Watch the sixth episode of our video series 'The Librarian's Talks: 6. 'Concentration camp literature'… in the CegeSoma Library

Given the "totalitarian" nature of Nazism and its extremely brutal modus operandi, which accumulated hostile elements as if for pleasure, places of detention and other "concentration camps" intended to accommodate the political enemies of the regime flourished across the Rhine from 1933 to 1945.

From the summer of 1940...and especially from the summer of 1941, the Belgian "political prisoners" multiplied, first filling the "German sections" of the country's prisons as well as the sinister forts of Breendonk and Huy, but also the cells of the various German police or parapolice departments, while waiting to be transferred and lost into the "night and fog" of the Third Reich’s concentration system. Although the exact number of these "non-racial" deportees is not known, the status of "political prisoner" was officially granted to 41,257 people in Belgium, and among them nearly 14,000 deaths were recorded.

From the summer of 1940...and especially from the summer of 1941, the Belgian "political prisoners" multiplied, first filling the "German sections" of the country's prisons as well as the sinister forts of Breendonk and Huy, but also the cells of the various German police or parapolice departments, while waiting to be transferred and lost into the "night and fog" of the Third Reich’s concentration system. Although the exact number of these "non-racial" deportees is not known, the status of "political prisoner" was officially granted to 41,257 people in Belgium, and among them nearly 14,000 deaths were recorded.

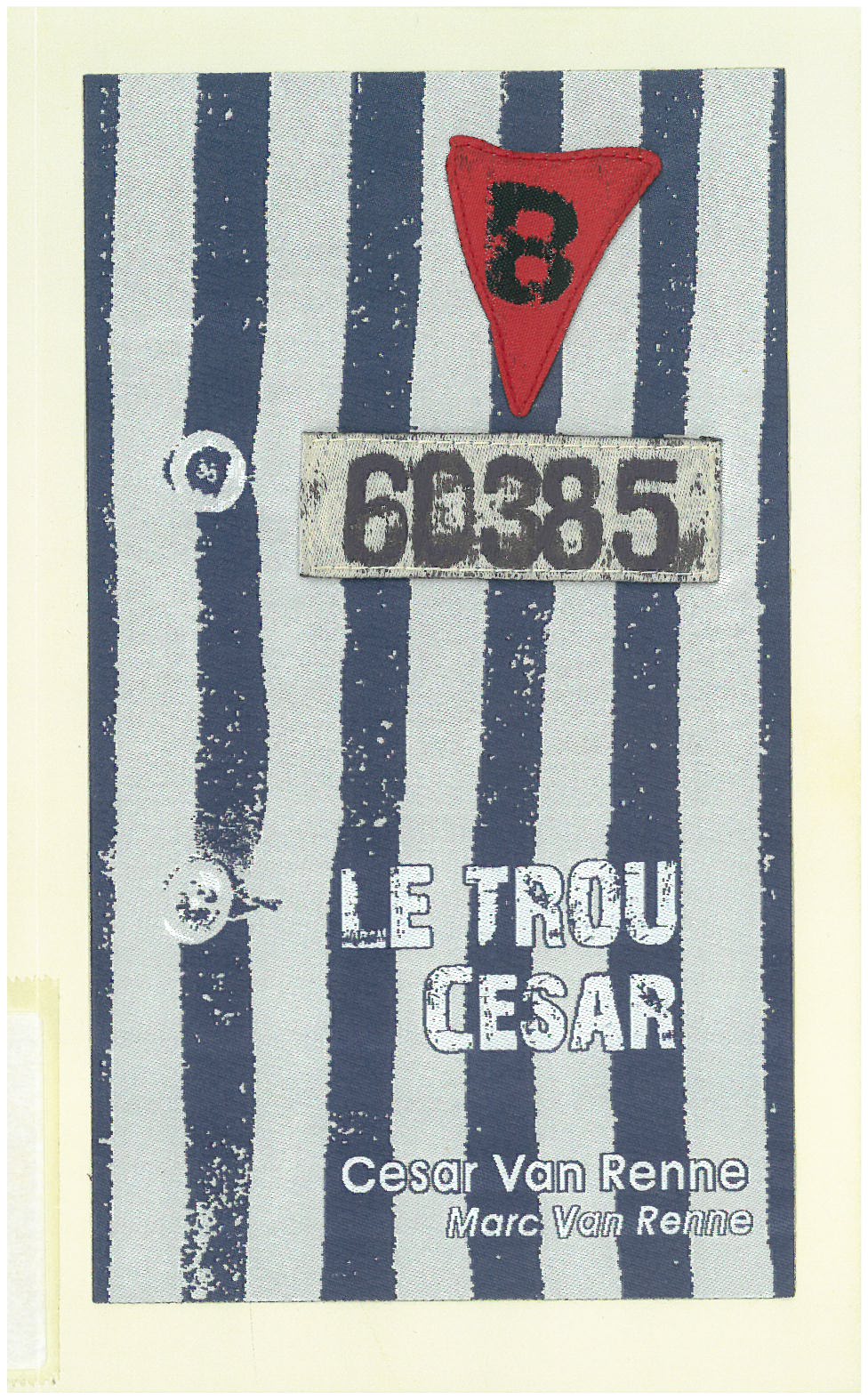

Some of the survivors - a rather small number - felt the need to write down the story of their tragic journey behind barbed wire, and their published testimonies can mostly be found in the CegeSoma's collections.

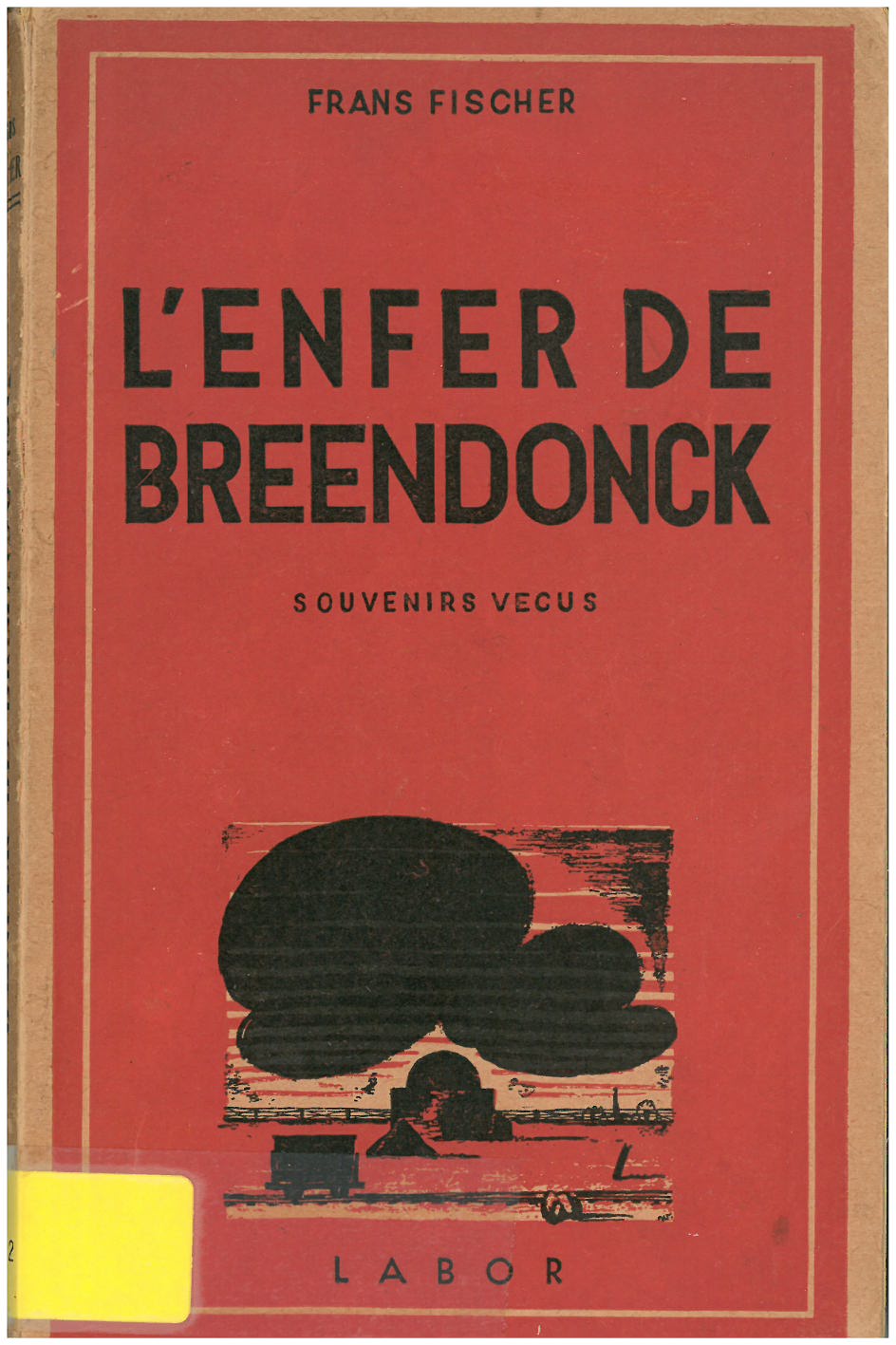

The first testimonies of "concentrationaries" are published quite early, from the autumn of 1944, and in general they are the work of former Breendonk inmates released by the enemy and present in Belgium at the Liberation, whether it be Frans Fischer (L'enfer de Breendonck-1944), Boris Solonevitch (Breendonck, camp de tortures et de mort-1944) or Victor Trido (Breendonck, camp du silence, de la mort et du crime-1944). All these works, generally written in French at the beginning, were translated into Dutch. Then, a little later, after the collapse of Hitler’s Reich, we see different books appear, testimonies of former " political " prisoners either from Dachau, or Buchenwald (long considered the most terrible and best known camp...), Ravensbrück, etc.

The first testimonies of "concentrationaries" are published quite early, from the autumn of 1944, and in general they are the work of former Breendonk inmates released by the enemy and present in Belgium at the Liberation, whether it be Frans Fischer (L'enfer de Breendonck-1944), Boris Solonevitch (Breendonck, camp de tortures et de mort-1944) or Victor Trido (Breendonck, camp du silence, de la mort et du crime-1944). All these works, generally written in French at the beginning, were translated into Dutch. Then, a little later, after the collapse of Hitler’s Reich, we see different books appear, testimonies of former " political " prisoners either from Dachau, or Buchenwald (long considered the most terrible and best known camp...), Ravensbrück, etc.

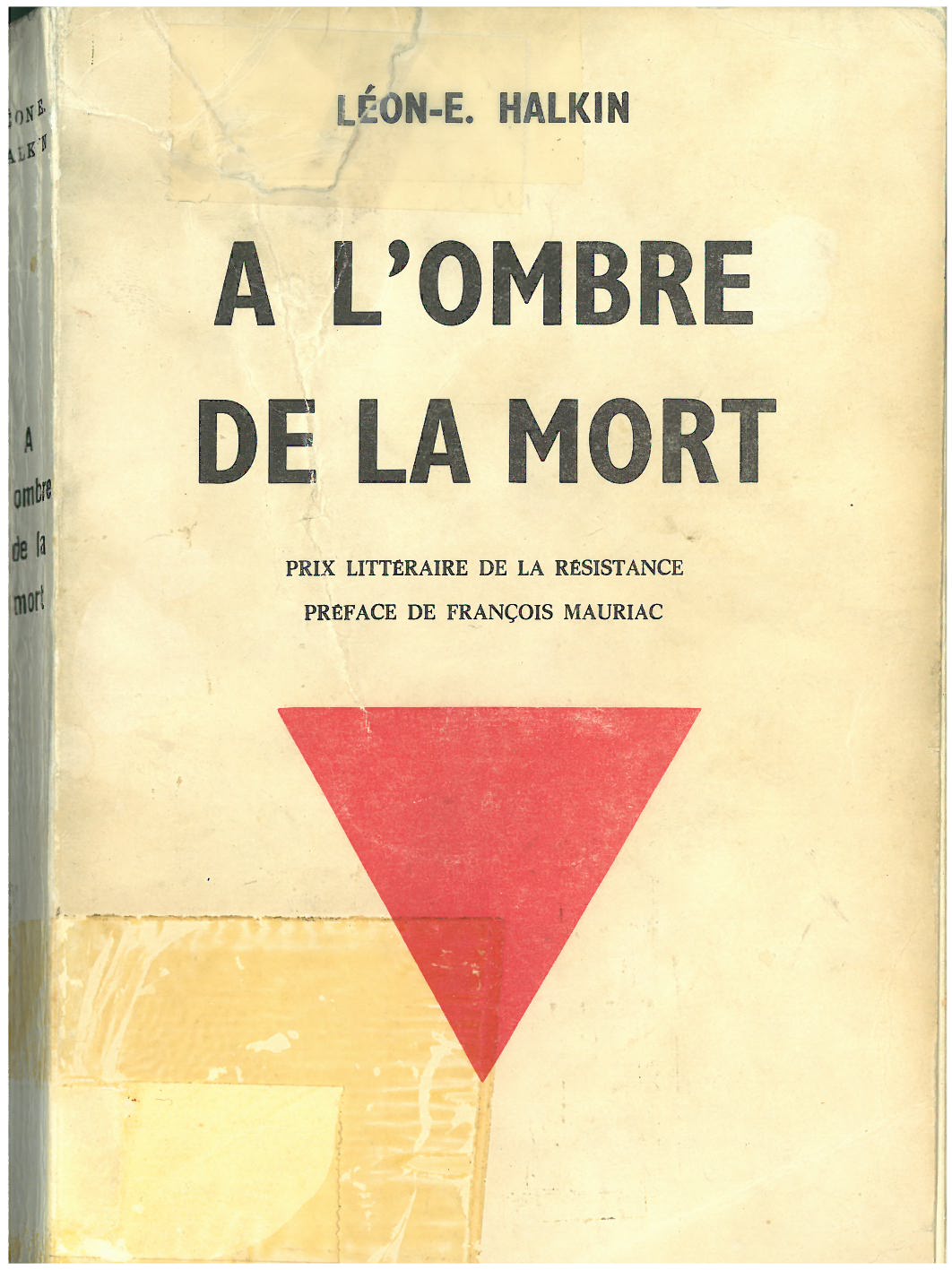

We can mention here the rather exemplary writings of Omer Habaru (Les triangles rouges-1946) or those, a little later but brilliant in every sense of the term, by Léon-Ernest Halkin (A l'ombre de la mort-1947). This type of testimonial literature, sometimes with militant intentions ("Never again!"), will long persist in the wake of associations of "old-timers" (such as R. Buelens, with De concentratiekampen en de gedetineerden-1970, published by the Nationale Confederatie den Politieke Gevangenen).

We can mention here the rather exemplary writings of Omer Habaru (Les triangles rouges-1946) or those, a little later but brilliant in every sense of the term, by Léon-Ernest Halkin (A l'ombre de la mort-1947). This type of testimonial literature, sometimes with militant intentions ("Never again!"), will long persist in the wake of associations of "old-timers" (such as R. Buelens, with De concentratiekampen en de gedetineerden-1970, published by the Nationale Confederatie den Politieke Gevangenen).

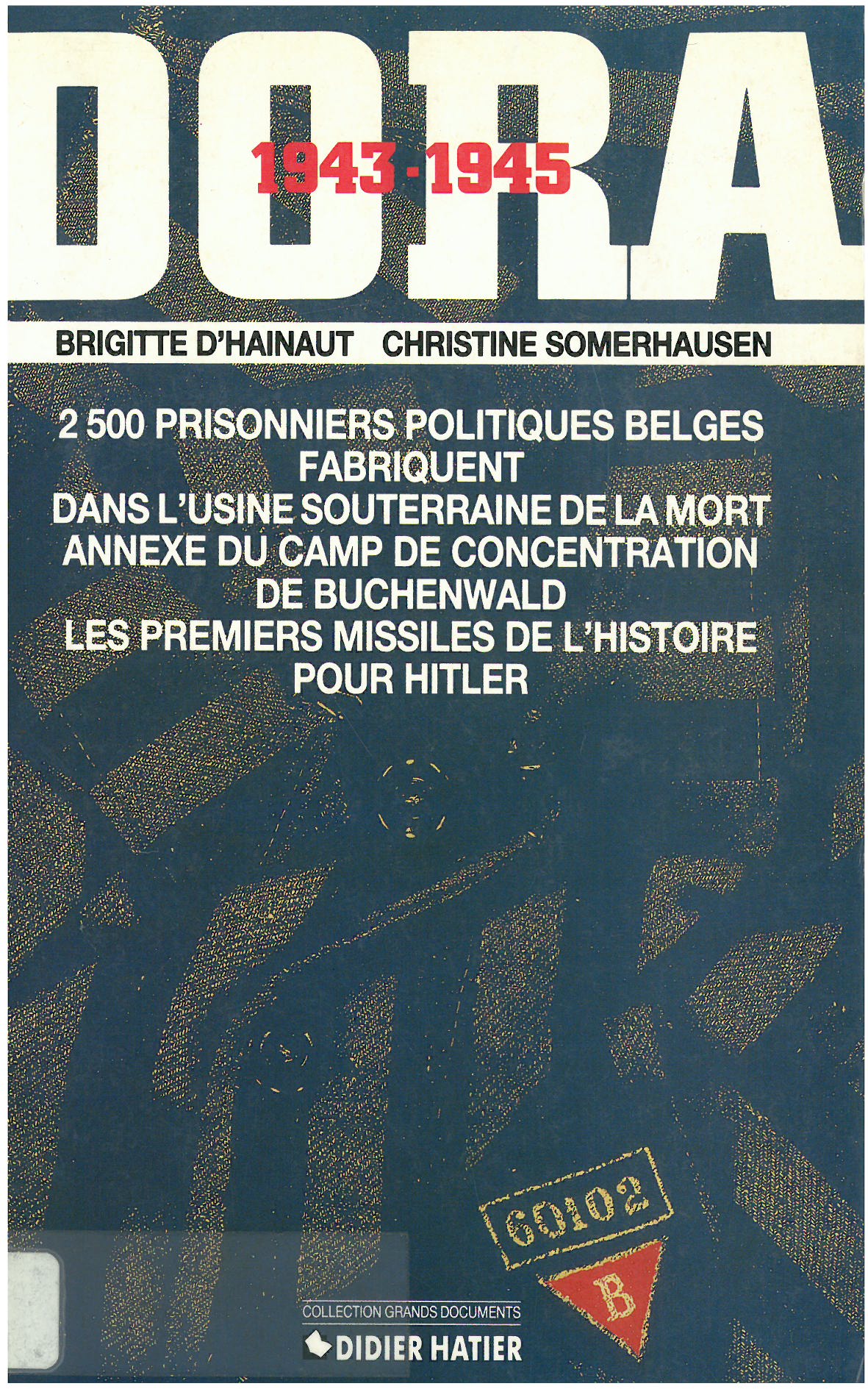

A generation later, there will appear more scientific approaches to the concentration camp phenomenon (but not always without underlying political intentions) such as those of Daniel Rochette and Jean-Marcel Van Hamme ("Les Belges à Buchenwald et dans ses commandos extérieurs", 1976) or Christine Somerhausen and Brigitte d'Hainaut (Dora 1943-1945-1991).

A generation later, there will appear more scientific approaches to the concentration camp phenomenon (but not always without underlying political intentions) such as those of Daniel Rochette and Jean-Marcel Van Hamme ("Les Belges à Buchenwald et dans ses commandos extérieurs", 1976) or Christine Somerhausen and Brigitte d'Hainaut (Dora 1943-1945-1991).

Finally, in the 1990s, we see the emergence of purely scientific contributions, the process of historicization of the concentration camp phenomenon being at that time in the process of completion. The works of Patrick Nefors (Breendonk, 1940-1945. De geschiedenis-2004, with a French language edition published by Racine in 2005) or by Gie van den Berghe (Getuigen. Een case-study over ego-documenten. Bibliografie van ego-documenten over de nationaal-socialistische kampen en gevangenissen, geschreven of getekend...-1995).

Finally, in the 1990s, we see the emergence of purely scientific contributions, the process of historicization of the concentration camp phenomenon being at that time in the process of completion. The works of Patrick Nefors (Breendonk, 1940-1945. De geschiedenis-2004, with a French language edition published by Racine in 2005) or by Gie van den Berghe (Getuigen. Een case-study over ego-documenten. Bibliografie van ego-documenten over de nationaal-socialistische kampen en gevangenissen, geschreven of getekend...-1995).

It should be pointed out that not all of the life stories of these very special prisoners have been published: a certain number of them are listed in our sub-section " Personal Diaries " and are perhaps waiting for a valiant historian to bring them to light and - who knows - to make them available to the " general educated public ", with the necessary critical apparatus.

It should be pointed out that not all of the life stories of these very special prisoners have been published: a certain number of them are listed in our sub-section " Personal Diaries " and are perhaps waiting for a valiant historian to bring them to light and - who knows - to make them available to the " general educated public ", with the necessary critical apparatus.

Researchers tempted by this problematic, but still uninitiated, can usefully refer to number 14-15 of the series Jours de guerre, entitled Jours barbelés. It presents a good synthesis of a question that has until now been addressed mostly from a Francophone perspective...