Leon Degrelle : A Paper Führereke (« Little Führer ») ...in the CegeSoma Library

Leon Degrelle : A Paper Führereke (« Little Führer ») ...in the CegeSoma Library ... Under this title, we invite you to discover the fifth theme of our series 'The Librarian's talks'. Each theme will be the occasion to dive into our collections and will be illustrated by a video and a text to complete the information contained therein.

Watch the fifth episode of our video series 'The Librarian's Talks: 5. Leon Degrelle : A Paper Führereke (« Little Führer ») ...in the CegeSoma Library'.

Why Degrelle? Why still speak about Léon Degrelle, former "Head of the Rexist Movement", champion of the "Crusade against Bolshevism" on the Eastern Front and long since deceased? Because in this year 2021 "national-populisms" are on the rise all over Europe? That it is good to remember, in these times, "the darkest hours of our history"? Well, not really. This is not our intention here. Our ambitions are more measured and probably more realistic. The character, as such, occupies in our Library a significant part of the shelves: no less than 97 writings are directly devoted to him, from the scientific work to the partisan pamphlet, and the titles specifically related to his Movement or to his fights on the Russian front are even more numerous. At this point, it seems likely that the steady flow of publications will continue unabated, since the most recent book productions (in both national languages) are only two or three years old. In short, historiographically speaking, the corpse of the Chief of Rex is still stirring. That is why we undertake to draw the attention of the "general educated public" and interested persons to this presence in our Library. A presence, that after the Liberation, many would have found unwelcome, even sacrilegious, since that name was so hated at the time...

Should we recall it? His presence (in 8vo or quarto-sized books!) within the walls of our institution owes a great deal to the offices of Dr. Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda. It was those who, at the outset, gave Degrelle the opportunity to exist thanks to the Ordre Nouveau media, and from 1943-1944 made him a hero (a herald?) in the small world of European collaboration, when the military situation was evolving more and more unfavorably for Germany and its supporters needed to be "doped up" by "edifying examples" created for the occasion. We will remember for a long time, in our homes, his smiling face, but in SS uniform, on the front page of the widely distributed magazine Signal one day in 1944…

Should we recall it? His presence (in 8vo or quarto-sized books!) within the walls of our institution owes a great deal to the offices of Dr. Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda. It was those who, at the outset, gave Degrelle the opportunity to exist thanks to the Ordre Nouveau media, and from 1943-1944 made him a hero (a herald?) in the small world of European collaboration, when the military situation was evolving more and more unfavorably for Germany and its supporters needed to be "doped up" by "edifying examples" created for the occasion. We will remember for a long time, in our homes, his smiling face, but in SS uniform, on the front page of the widely distributed magazine Signal one day in 1944…

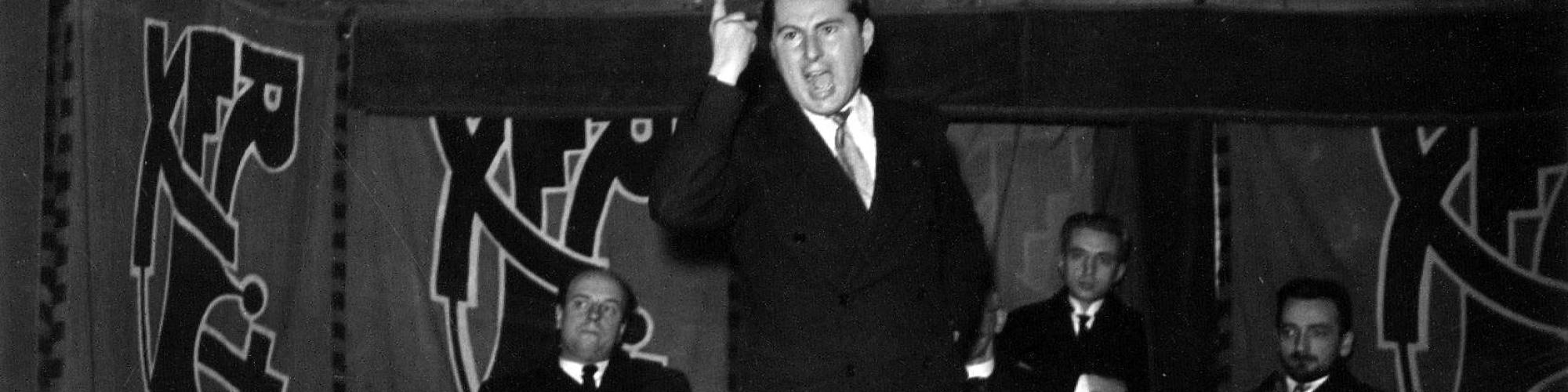

This suited perfectly the extrovert character of this man who, moreover, by his nature and his socio-professional past or his political commitment, could in turn, according to the circumstances, profile himself as either a journalist, a media man, an inspired tribune, a war leader, etc... And make an illusion in the eyes of a certain public, always fascinated by the media rumor when it promoted the image of the "strong man".

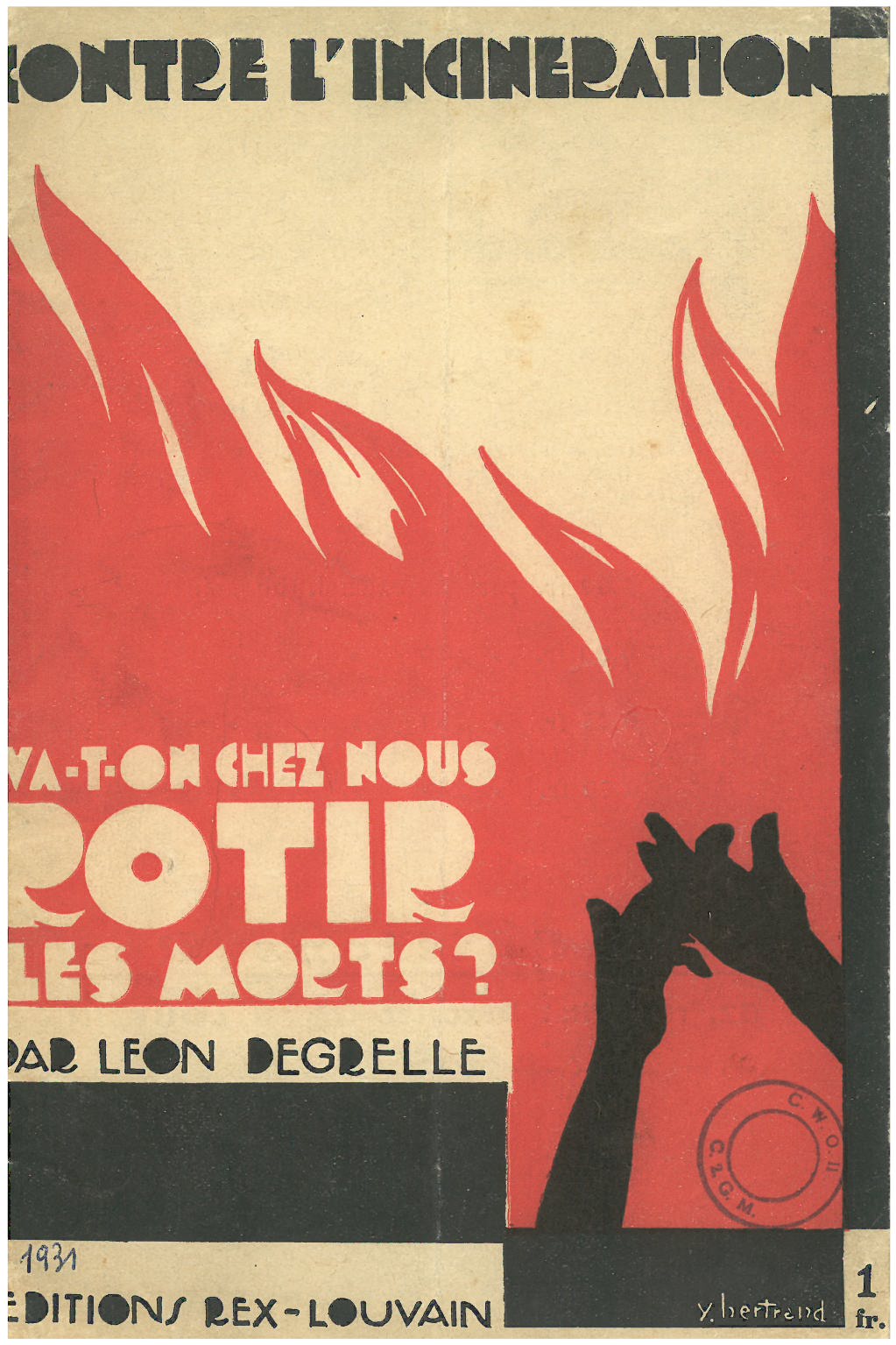

One thing is certain: his writings are not rare, his literary career spanning more than 60 years. At the beginning, we can pinpoint quite a few pamphlets concocted while he was still working for the Action Catholique de la Jeunesse Belge or/and the Editions "Rex". So let us highlight in our collections, among others, Les Taudis (1929), Les Flamingants (1930), Vive le Roi ! (1931) and Contre l'incinération. Vera-t-on chez nous rôtir les morts? (1931)... Let us skip some… " and from the best "! Later, after having detached himself from the traditional Catholic family in 1935-1936 to play the tribune of the people against "les pourris" (« the rotten ones »), he was seen devoting himself to an aggressively polemical and openly pamphleteering literature, with the series of his "J'accuse" (« I accuse ») booklets : J’accuse M. Segers d’être un cumulard, un bankster, un pillard d’épargne et un lâche (« I accuse Mr. Segers of being a cumulard, a bankster, a thief of savings and a coward »), J’accuse Marcel-Henri Jaspar, menteur, pillard et faussaire (« I accuse Marcel-Henri Jaspar, a liar, a looter and a forger »), etc, etc… , .

One thing is certain: his writings are not rare, his literary career spanning more than 60 years. At the beginning, we can pinpoint quite a few pamphlets concocted while he was still working for the Action Catholique de la Jeunesse Belge or/and the Editions "Rex". So let us highlight in our collections, among others, Les Taudis (1929), Les Flamingants (1930), Vive le Roi ! (1931) and Contre l'incinération. Vera-t-on chez nous rôtir les morts? (1931)... Let us skip some… " and from the best "! Later, after having detached himself from the traditional Catholic family in 1935-1936 to play the tribune of the people against "les pourris" (« the rotten ones »), he was seen devoting himself to an aggressively polemical and openly pamphleteering literature, with the series of his "J'accuse" (« I accuse ») booklets : J’accuse M. Segers d’être un cumulard, un bankster, un pillard d’épargne et un lâche (« I accuse Mr. Segers of being a cumulard, a bankster, a thief of savings and a coward »), J’accuse Marcel-Henri Jaspar, menteur, pillard et faussaire (« I accuse Marcel-Henri Jaspar, a liar, a looter and a forger »), etc, etc… , .

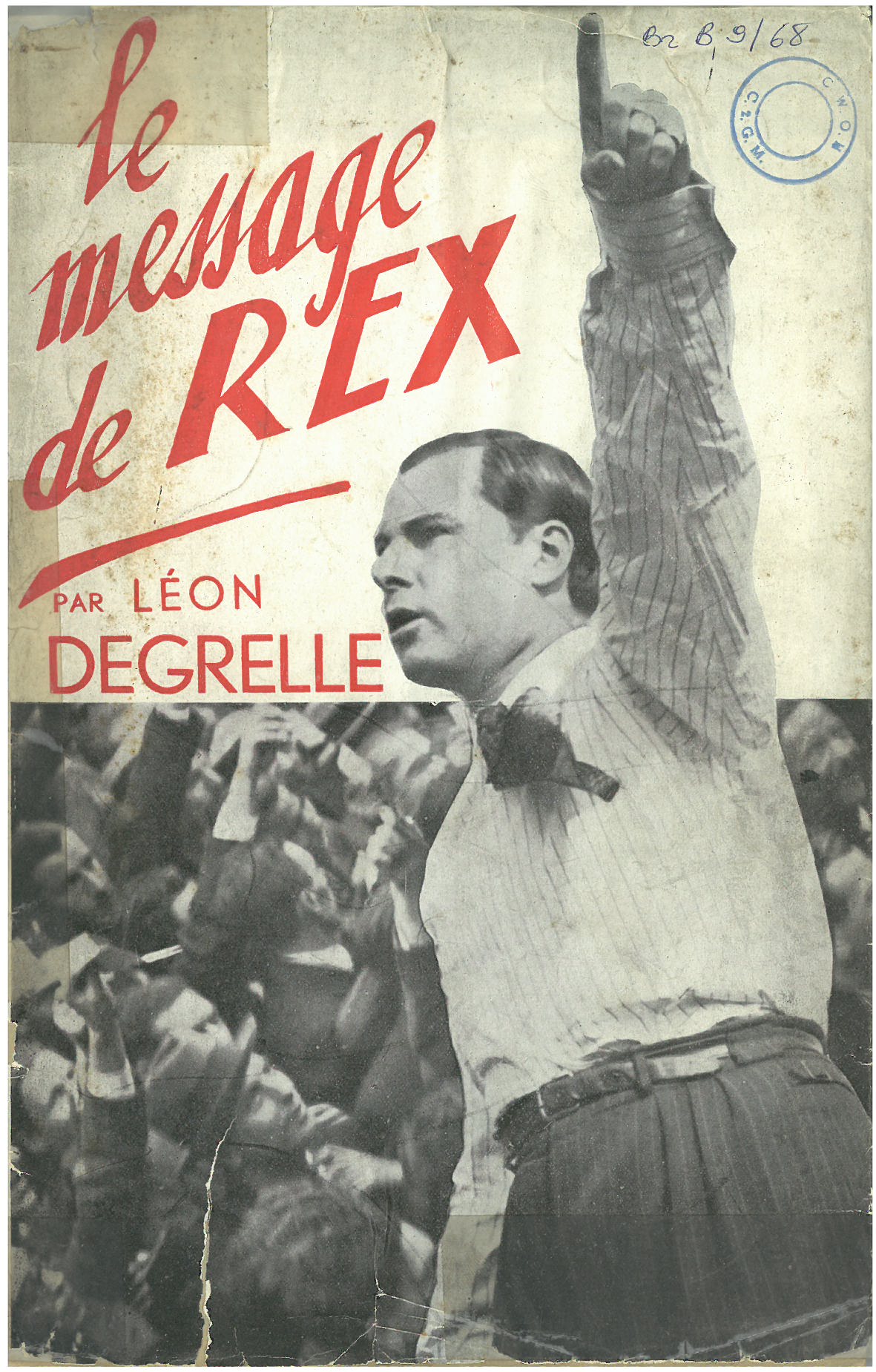

Shortly after his electoral breakthrough, wanting to give his movement some intellectual or ideological consistency he applied himself to write for the masses of laymen attracted by his media-political hubbub Le Message de Rex (1936) as well as La Révolution des âmes (« The Revolution of the Souls ») (1938), which his opponents maliciously dubbed 'La Révolution des ânes' (« The revolution of the Donkeys »). During the Occupation, as a militant committed to "European" National Socialism, he naturally did not remain silent, and during these 'years of lead' we record his modest (ahem!) Degrelle avait raison! (1940), his largely dramatized early war memories of La guerre en prison (1941) and (already!) with Feldpost (1944), his recollections as a veteran of the Russian front.

Shortly after his electoral breakthrough, wanting to give his movement some intellectual or ideological consistency he applied himself to write for the masses of laymen attracted by his media-political hubbub Le Message de Rex (1936) as well as La Révolution des âmes (« The Revolution of the Souls ») (1938), which his opponents maliciously dubbed 'La Révolution des ânes' (« The revolution of the Donkeys »). During the Occupation, as a militant committed to "European" National Socialism, he naturally did not remain silent, and during these 'years of lead' we record his modest (ahem!) Degrelle avait raison! (1940), his largely dramatized early war memories of La guerre en prison (1941) and (already!) with Feldpost (1944), his recollections as a veteran of the Russian front.

But it is especially during his post-war Spanish exile that he will prove to be the most prolific (it is true that he had to occupy his forced leisure...).

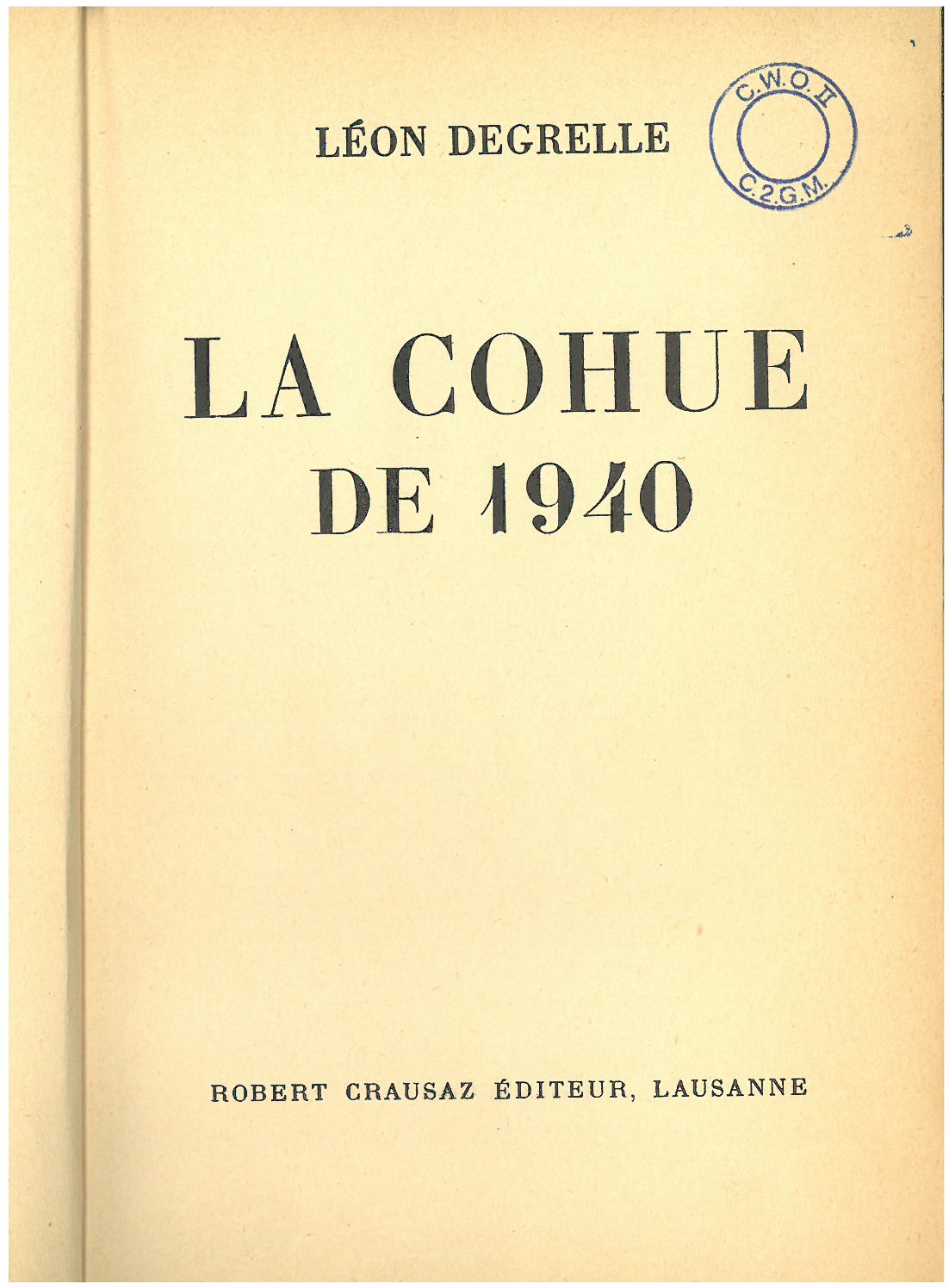

His writings turn apologetic with La cohue de 1940 (1949), undoubtedly his greatest publishing success, a book in which he tries to "muckrake" scores of prominent politicians, still in good standing at the time in post-war Belgium. They then become lyrical with Front de l'Est 1941-1945 (1969), or Hitler pour 1000 ans (1969), and veer to plain ranting in the two volumes of his final essays with historical pretensions entitled (no kidding!) Hitler démocrate (2002 - 2 vol.).

His writings turn apologetic with La cohue de 1940 (1949), undoubtedly his greatest publishing success, a book in which he tries to "muckrake" scores of prominent politicians, still in good standing at the time in post-war Belgium. They then become lyrical with Front de l'Est 1941-1945 (1969), or Hitler pour 1000 ans (1969), and veer to plain ranting in the two volumes of his final essays with historical pretensions entitled (no kidding!) Hitler démocrate (2002 - 2 vol.).

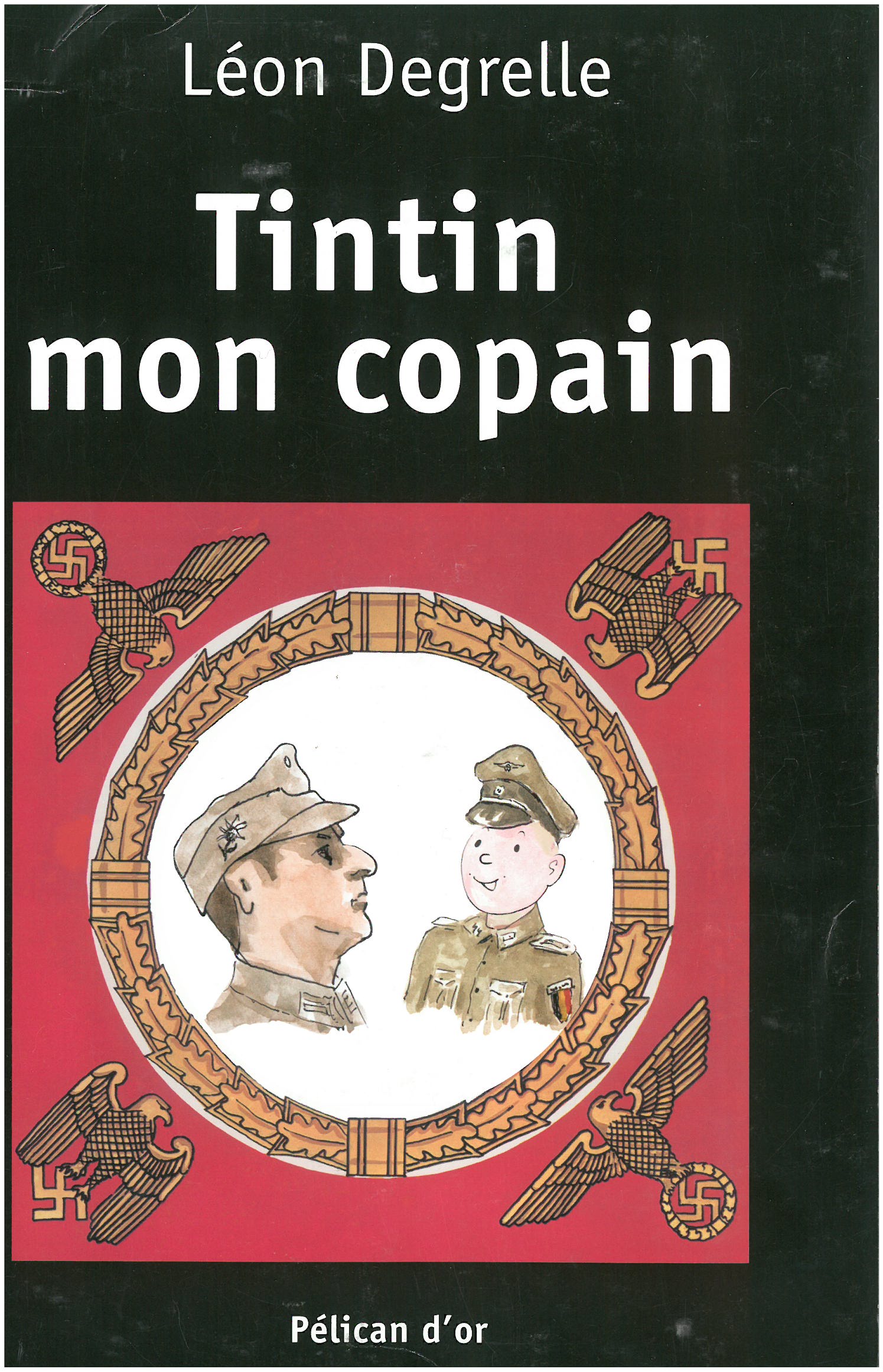

After his death, in 2000, his friends edited an unpublished text of his, Tintin mon copain (Tintin my friend), intended as a wink to "his friend Hergé", but although richly illustrated, the humorous charge that it supposedly contains is rather flat. He could have left it at that, but in the meantime he had felt the need to add his voice to the chorus of deniers of the Judeocide, with his Lettre à mon cardinal (1975) and especially his Lettre au pape à propos d'Auschwitz (1975), showing that he had forgotten nothing and learned nothing.

After his death, in 2000, his friends edited an unpublished text of his, Tintin mon copain (Tintin my friend), intended as a wink to "his friend Hergé", but although richly illustrated, the humorous charge that it supposedly contains is rather flat. He could have left it at that, but in the meantime he had felt the need to add his voice to the chorus of deniers of the Judeocide, with his Lettre à mon cardinal (1975) and especially his Lettre au pape à propos d'Auschwitz (1975), showing that he had forgotten nothing and learned nothing.

This non-exhaustive bibliography of his works shows that Degrelle knew how to talk about himself. Unfortunately, other people, polemicists or historians, had the same idea. And the literary harvest is just as fruitful in this respect.

Writing about Degrelle

During his active political phase (roughly 1935-1945), writings naturally accumulated around his name, whether by his supporters (such as José Streel, in Ce qu'il faut penser de Rex (1935) or Usmard Legros, in Un homme, un chef : Léon Degrelle (1937), not to invoke the ghosts of a Robert Brasillach and his Léon Degrelle et l'avenir de Rex (1936)) or his many opponents (Robert de Vroylande, with the ferocious Quand Rex était petit (1936) and the more vehement Léon Degrelle Pourri (1936), or Frédéric Denis, with his - somewhat premature - Rex est mort (1937)). If there is, in general, relatively little reliable information to be drawn from these committed publications, they are no less interesting for grasping the spirit of an era and, as long as Degrelle was alive, they sometimes enjoyed a long literary posterity in a more elaborate form. One thinks of the works of Charles d'Ydewalle (Degrelle ou la triple imposture (1968)) or of Pol Vandromme (Le loup au cou de chien. Degrelle au service d'Hitler (1978)), without forgetting L'aventure rexiste-Essai by Robert Pfeiffer and Jean Ladrière (1966), which presents a more "historicized" turn.

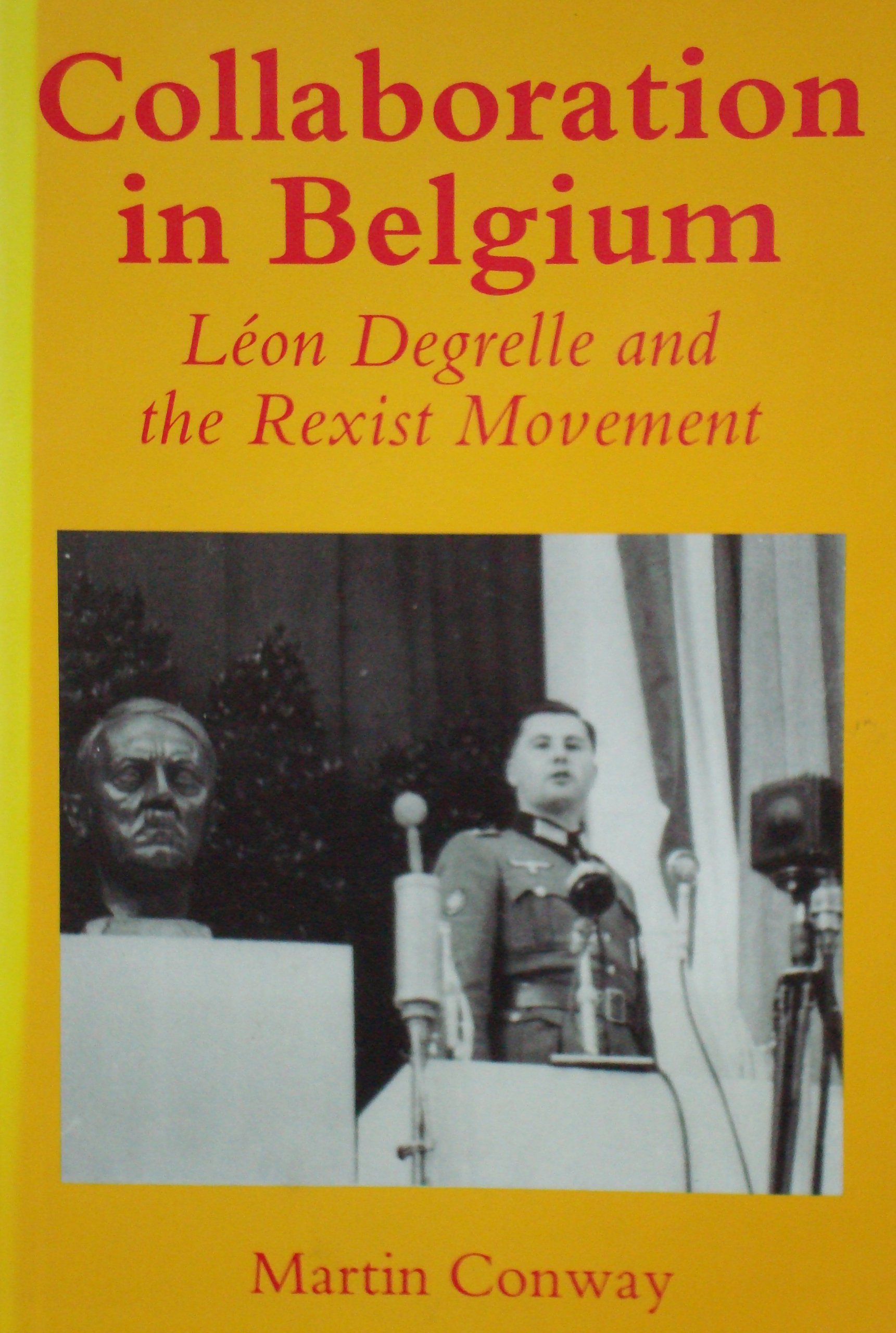

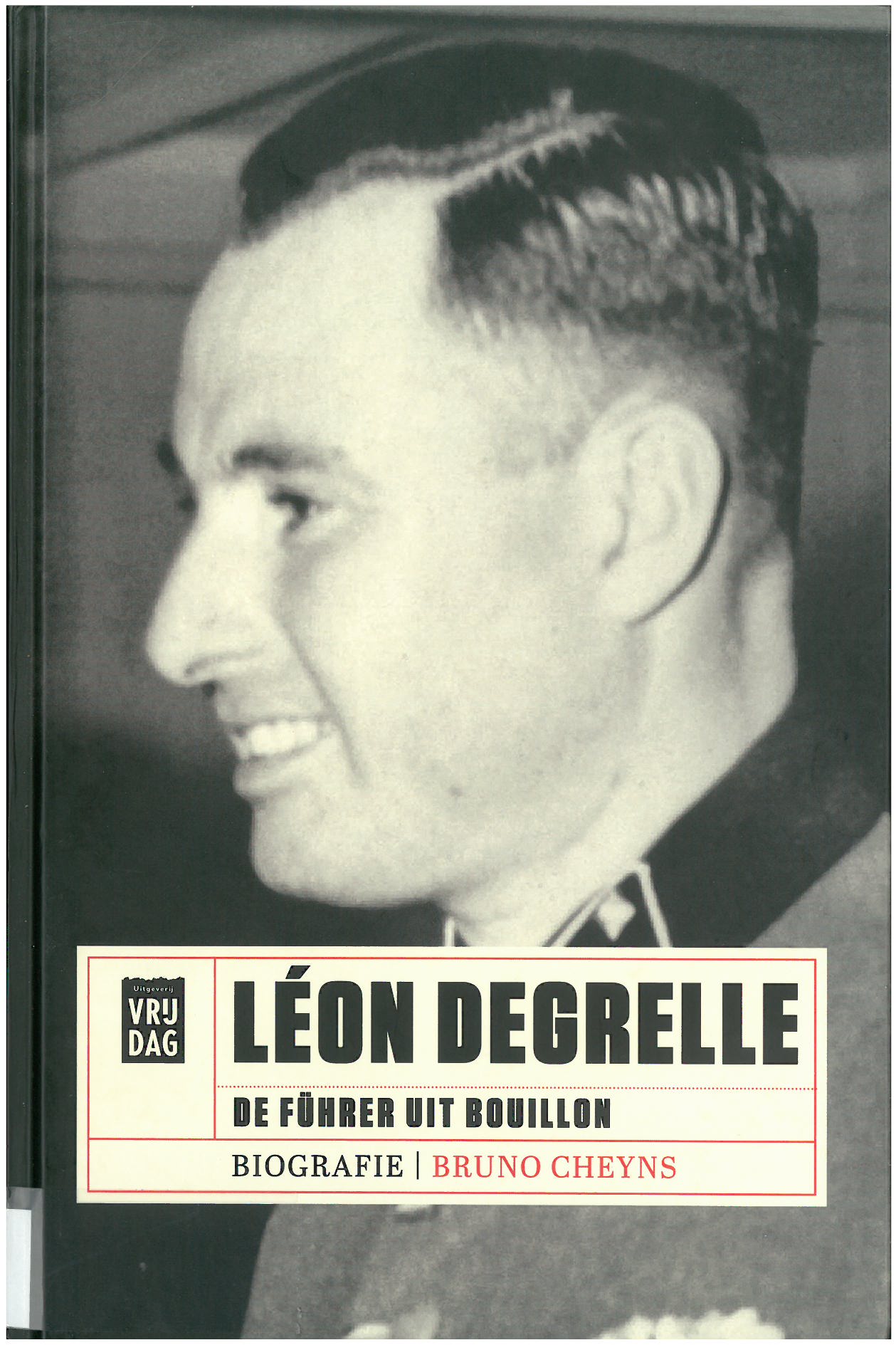

But truly scientific productions on rexism and its leader only began in earnest with the study of the Frenchman Jean-Michel Etienne, Le mouvement rexiste jusqu'en 1940, published symptomatically in Paris in 1968. Then came, no doubt indirectly encouraged by Maurice De Wilde's television broadcasts in the early 1980s, a succession of quality publications: Jean-Marie Frérotte's Léon Degrelle, le dernier fasciste (1987), Martin Conway's Collaboration in Belgium : Léon Degrelle and the Rexist Movement (1993), Eddy De Bruyne and his thorough work on the Walloon Legion or Rexism in the emigration across the Rhine, and (finally!) Bruno Cheyns and his excellent Léon Degrelle: De Führer uit Bouillon (2017).

But truly scientific productions on rexism and its leader only began in earnest with the study of the Frenchman Jean-Michel Etienne, Le mouvement rexiste jusqu'en 1940, published symptomatically in Paris in 1968. Then came, no doubt indirectly encouraged by Maurice De Wilde's television broadcasts in the early 1980s, a succession of quality publications: Jean-Marie Frérotte's Léon Degrelle, le dernier fasciste (1987), Martin Conway's Collaboration in Belgium : Léon Degrelle and the Rexist Movement (1993), Eddy De Bruyne and his thorough work on the Walloon Legion or Rexism in the emigration across the Rhine, and (finally!) Bruno Cheyns and his excellent Léon Degrelle: De Führer uit Bouillon (2017).

The latter examines especially the impact of the "Rex-leader" in the Flemish context, a hithertho little studied theme. This list is obviously not exhaustive, and, moreover, for lack of space, it does not take into account any of the articles written about him or his movement in scholarly journals or in the proceedings of academic conferences.

It is clear that the demon Degrelle is present within the walls of CegeSoma. But no fear, even if you wish to meet him: he is just a paper devil...and he cannot leave our reading room anyway!

A. Colignon