Spies and espionage in the CegeSoma Library (1) : From the First to the Second World War

"Spies and espionage in the CegeSoma Library (1) : From the First to the Second World War". Under this title, we invite you to discover the fifteenth theme of our series 'The Librarian's Talks'. Each theme will be an opportunity to dive into our collections and will be illustrated by a video and a text complementing the information found there.

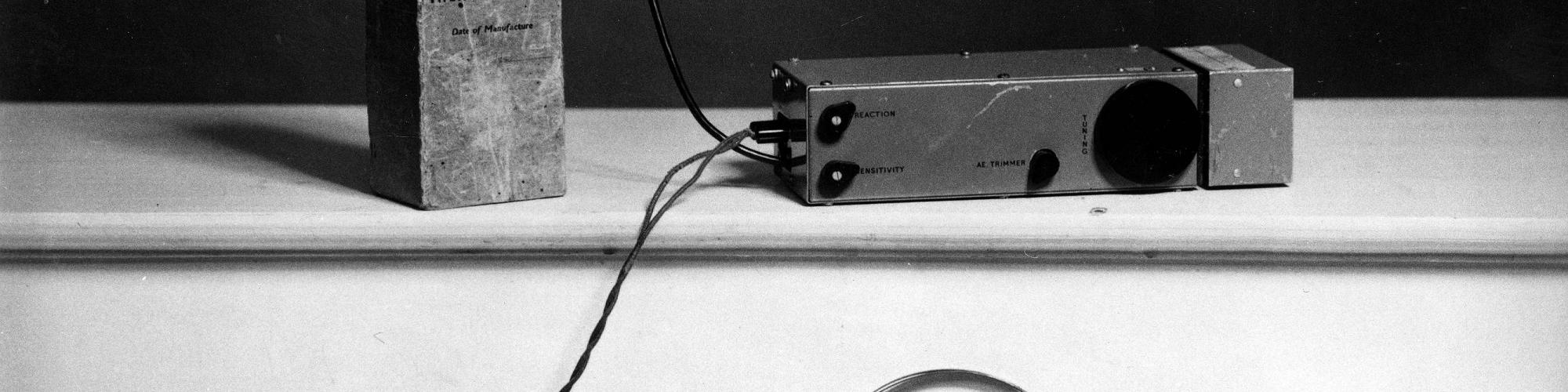

Watch the fifteenth video 'The Librarian's Talks: 15. Spies and espionage in the CegeSoma Library (1) : From the First to the Second World War".

Espionage has probably existed since the dawn of time. Or rather, ever since a human community with a modicum of organization (from tribes and city-states to empires), aware not only of itself but also of its divisions and the antagonistic forces that threaten it, has felt the need to protect itself from the dangers of existence by discreetly seeking information from the Other, the potential or actual enemy. In short, espionage is quite simply a desire for information, for intelligence (today, rather than espionage, aren't we more modestly talking about "intelligence services"?), and the actions linked to this desire can be traced in the West as much in the Old Testament as in Homer's Iliad. The remote Orient is of course no exception: several passages in the celebrated Chinese Art of War make unabashed reference to it. On the other hand, attitudes changed - at least in theory - during the Christian Middle Ages, when feudal society at its height was steeped in chivalric ideals. The profession of spy, then, found itself rather discredited, likened to a form of disloyal combat, if not a kind of treason. This didn't prevent it from being practised bravely in times of need, but no one boasted about it, and it remained so practically until the secularization of states from the 17th to the 19th centuries. This rather negative state of mind towards the honourable guild of spies and other intelligence agents only began to change in the 19th century, with conflicts increasingly involving populations in mass wars (French Revolution, American Civil War, Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871). Admittedly, the spy didn't become a hero overnight, but the lines began to shift, and from then on he was seen as an indispensable instrument of salvation, among others, for the national community. An instrument of salvation, by its very nature doomed to discretion, if not anonymity, and able to be adorned with the aura of an adventurer-which, in increasingly massified societies, can be seen as very attractive.

The colonial adventure further strengthened its role (albeit in a dotted line) on the world stage, with each major nation equipping itself with military attachés, as well as ethnographers, missionaries and geographers scattered around the globe, likely to play the role of discreet observers, or not, in the context of all-out rivalry between competing imperialisms.

Then came World War I, a new mass conflict, this time coupled with an industrial war involving the mobilization of all the energies of nations. And all the resources of espionage, which led to its definitive revaluation... and the emergence of a number of fantasies linked to the practice of this profession. While agents of the Intelligence Service or the 'Second Bureau' applied themselves to tasks that were sometimes quite modest, obscure and yet indispensable (counting German military convoys bound for the front from such and such a railway station...), a number of widely-heroized characters ended up emerging into the public eye, sometimes posthumously or with little connection to reality. For a Lawrence of Arabia, there were so many Margaretha Geertruida Zelle! Even she managed to become the spy Mata Hari for posterity ... after the execution post and thanks to a well-executed media campaign. But her colleagues were not always so 'lucky'.

Nevertheless, more than one of them ended up as cult-figures, something that would have been inconceivable a generation earlier. And if their activity was not always in the public eye, it had lost its character bordering on dishonour. In a way, the Resistance exonerated espionage...when it was carried out by 'nationals', driven by feelings of the highest civic-mindedness (if possible). The process in question has been studied in detail by Laurence van Ypersele and Emmanuel Debruyne in their study De la guerre de l'ombre aux ombres de la guerre (2005). And yet, even while being that, and being what he was, he retained an element of ambiguity, as well as a strange, slightly disquieting aura.

Nevertheless, more than one of them ended up as cult-figures, something that would have been inconceivable a generation earlier. And if their activity was not always in the public eye, it had lost its character bordering on dishonour. In a way, the Resistance exonerated espionage...when it was carried out by 'nationals', driven by feelings of the highest civic-mindedness (if possible). The process in question has been studied in detail by Laurence van Ypersele and Emmanuel Debruyne in their study De la guerre de l'ombre aux ombres de la guerre (2005). And yet, even while being that, and being what he was, he retained an element of ambiguity, as well as a strange, slightly disquieting aura.

The Second World War naturally followed in the footsteps of the secret Great War, with ideology thrown in for good measure. British Military Intelligence had the opportunity to shine in all its facets in its fight against the German services, assisted, sometimes from afar, by American and Soviet counterparts, with a number of old hands (such as Walthère Dewé) not hesitating to " get back in the saddle" twenty years later to fight against the Nazified Reich. This time, they witnessed the blossoming of a whole series of pro-Allied intelligence and action networks, even if it meant clashing with German spies...or pro-Nazi Belgian spies. The infamous Prosper De Zitter is a fairly good model, and a formidably effective one at that.

The Second World War naturally followed in the footsteps of the secret Great War, with ideology thrown in for good measure. British Military Intelligence had the opportunity to shine in all its facets in its fight against the German services, assisted, sometimes from afar, by American and Soviet counterparts, with a number of old hands (such as Walthère Dewé) not hesitating to " get back in the saddle" twenty years later to fight against the Nazified Reich. This time, they witnessed the blossoming of a whole series of pro-Allied intelligence and action networks, even if it meant clashing with German spies...or pro-Nazi Belgian spies. The infamous Prosper De Zitter is a fairly good model, and a formidably effective one at that.

With the war over, the typical Western spy, when he didn't belong to the Axis forces, could feel satisfied. His moral status had been consolidated for a long time to come, he was seen as an intrepid hero whose image would become the stuff of literature, and what's more, the Cold War was on the horizon: in high places, his services would still be needed!

Given these circumstances, it's hardly surprising that espionage has had a very respectable place in CegeSoma's library: several hundred titles in our collections are devoted to this theme for both world wars. We'll just mention a few must-haves for this theme in its Belgian context: the ever-helpful Fernand

Given these circumstances, it's hardly surprising that espionage has had a very respectable place in CegeSoma's library: several hundred titles in our collections are devoted to this theme for both world wars. We'll just mention a few must-haves for this theme in its Belgian context: the ever-helpful Fernand  Strubbe, Geheime oorlog 40/45. De Inlichtings-en Actiediensten in Belgie -1992 (translated in 2000 as Services secrets belges 1940-1945) and the essential Gedenkboek Inlichtings-en Actie Agenten published in 2015 under the auspices of Roger Coekelbergs, who was "one of the house". And of course the excellent contribution by Emmanuel Debruyne entitled La guerre secrète des espions belges, 1940-1944 (The Secret War of Belgian Spies, 1940-1944), fruit of his PhD (2008).

Strubbe, Geheime oorlog 40/45. De Inlichtings-en Actiediensten in Belgie -1992 (translated in 2000 as Services secrets belges 1940-1945) and the essential Gedenkboek Inlichtings-en Actie Agenten published in 2015 under the auspices of Roger Coekelbergs, who was "one of the house". And of course the excellent contribution by Emmanuel Debruyne entitled La guerre secrète des espions belges, 1940-1944 (The Secret War of Belgian Spies, 1940-1944), fruit of his PhD (2008).

And then there's the Cold War period, with its rich harvest of titles. But that's another story, which we'll get to shortly.